As a nation-state where the indigenous population has been denied de-colonization and self-determination, alienation from land has been among Maori grievances since the signing of Te Tiriti o Waitangi in 1840, which had contrarily promised Maori sovereignty over their lands. Resistance to land alienation has also been a prominent theme of Maori activism as the last resort to resist colonization and the settlers disregard of Te Tiriti and Maori rights. The 1970’s particularly saw the unification and politicization of Maori through activism to resist policies which discrimination against Maori. There has gradually been increasing recognition of Maori rights since, the returning of land

Maori activism has not been restricted to land, yet for simplicity this blog post will focus on activism around land, particularly 3 examples from the 1970’s – the 1975 Land March, the protests at Raglan beginning the same year and the occupation of Bastion Point in 1977.

1975 Land March

The 73 year long Land Wars (1843-1916) initiated by settlers to acquire Maori land (Walker 2004, 135), accompanied by over a century of imperialist policies designed for the same purpose (Walker 1984, 277), had gradually worked to evict Maori off their land and register it under the possession of settlers or the Crown. Maori resistance to land alienation unified into a land-rights movement in 1975 named Te Roopu o te Matakite, particularly in response to the 1967 Maori Affairs Amendment Act which was dubbed ‘the last land grab’ by activists due to its purpose being to justify the confiscation of Maori land (Walker 2004, 212). In efforts to preserve the remaining one million hectares which Maori owned, Te Roopu o te Matakite led a 30,000 strong hikoi to parliament under the slogan ‘not one more acre of land.’

It may be seen that the marches had failed as no land was directly returned as a result and policy recommendations made by Te Roopu o te Matakite were not adopted. However as a consequences of the Land March Maori across New Zealand were both politicized and united to unprecedented levels in the modern era (Walker 2004, 214). The political-spiritual ideology advocated by Te Roopu o te Matakite consolidated Maori across iwi (Taonui 239), and the galvanizing political discussions which ensued nightly on guest maraes allowed those who had been disconnected or felt distanced from Maori culture to immerse themselves, learn about their roots and draw inspiration from the Maori part of their identity which the colonial government had been working to alienate Maori from (Harris 2004, 75). Various other activists groups had formed inspired by the hikoi to conduct marches and occupations of their own (Taonui 239). The stories of activism in Raglan and Bastion Point particularly display how the land-rights movement in this period had been vital overall in securing recognition of Maori rights and reacquiring Maori land.

Raglan

In 1972 Tuaiwa (Eva) Rickard and the people of Tainui Awhiro underwent a campaign seeking the return of the Raglan Golf Course. During WWII Tainui Awhiro had been forced off of Raglan for the construction of a military airfield requiring iwi to leave their homes, marae, cultivations and urupa (cemetery), under the agreement that the land would be returned and no harm would come to the urupa (Harris 2004, 60). At the end of the war, however, instead of the land being returned to Tainui Awhiro, Raglan was leased to the Raglan Golf Club to create a golf course, with Maori homes, marae and urupa being demolished without any reference to iwi.

Eva became a leading figure in the Land March in 1975 which allowed her to network and enlist support for her campaign (Harris 2004, 62). Later that year with the support she had gathered Eva led an occupation of the golf course resulting in her arrest. Three subsequent offers by the Crown followed proposing Tainui Awhiro buy back the land which had been confiscated off of them, yet all were refused by iwi (Taonui 2013, 240). Eva did not feel iwi should pay for land which rightfully belonged to them and two years later the golf course was re-occupied with support from 250 protesters involved in the land-rights movement, once again leading to their arrests (Harris 2004, 62). The Government offered Tainui Awhiro to buy the land again yet with iwi refusing to compromise their position the Government reworked their position until Raglan was finally returned to Tainui Awhiro at no cost in 1987.

Bastion Point

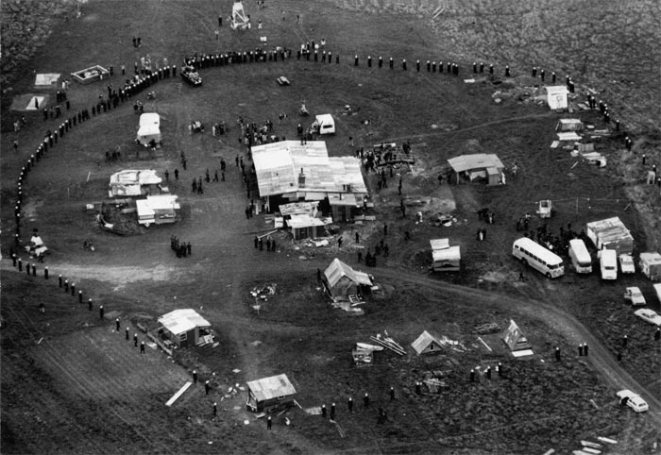

The occupation of Bastion Point by Joe Hawke and the Orakei Maori Action Group in a similar manner displayed the role Maori activism of this period played in reacquiring Maori land. Hawke had also been politicized during the Land March and continued the Maori activist ethos by organizing an occupation at Bastion Point in 1977 following announcements the previous year by the government to subdivide 24 hectares of land at Bastion Point (Walker 2004, 215). The discriminatory policies aimed at confiscating Maori land had left Ngati Whatua only three acres at Orakei by 1928 (Harris 2004, 79). Showing complete disregard for iwi a sewage pipe was built across the front of their marae in 1912 discharging untreated sewage into a bay which Ngati Whatua had traditionally interacted with (Harris 2004, 82). Through using the pretext of protecting Maori health Ngati Whatua were evicted off of their remaining land in 1951 with their homes and marae bulldozed and burned, rendering it seemingly hopeless to retain their tribal homeland (Harris 2004, 82-83).

The occupation in 1977 called for the return of all 72 hectares of Ngati Whatua land at Bastion Point (Taonui 2013, 242). In response the crown offered Ngati Whatua some land returned yet iwi would also be saddled with $200,000 of debt to pay for development costs – similarly to Raglan the offer was refused.

Though financial hardships made the occupation difficult for activists, the protests only came to end after 506 days when 600 police officers were called to end the occupation by force (Harris 2004, 84). Two further occupations took place in 1982 both leading to arrests. When the Waitangi Tribunal jurisdictions were amended in 1985, Hawke lodged a claim at the tribunal, making Orakei the first historical claim the tribunal heard (Harris 2004, 86). The recommendations made by the tribunal led to the 1991 treaty settlement which included the return of 16 hectares, $3 million in compensation and joint management over 48 hectares at Bastion Point (Taonui 2013, 242).

It may be seen that it was not activism which led iwi to regain Bastion Point but the Waitangi Tribunal, yet this would forget that the tribunal itself was formed as the result of activism by Nga Tamatoa (Walker 2004, 212). Furthermore, Raglan highlights how the pressure applied by activism without compromising iwi demands can lead to the gradual recognition of Maori land-rights. It may not be unreasonable to assume the occupations at Bastion Point pressured the Government to recognize Maori land grievances. The protests at Raglan and Bastion Point did not seem as though they were going to end unless resolved and due to the uncompromising position of activists this meant iwi had to be compensated for their losses. In this manner Activism can often force grievances into political discussions and be a tool for marginalized voices to gain representation. The Tribunal alone does not have any power to settle treaty claims but only to write reports which in ways can pressure the government to act. Yet it is difficult to assume the Crown was eventually going to return confiscated land in these regions due to how hard activists had to battle to have their land-rights under the treaty recognized.

Bibliography

Harris, A. (2004). Hikoi: Forty Years of Maori Protest. Wellington: Huia Publishers.

Taonui, R. (2013). Maori Urban Protest Movements. In Danny Keenan (Ed.), Huia Histories of Maori: Nga Tahuhu Korero (pp.229-259). Wellington: Huia Publishers.

Walker, R. (2004). Ka Whawhai Tonu Matou: Struggle Without End (Rev. ed.). Auckland: Penguin.

Walker, R. (1984). The Genesis of Maori Activism. The Journal of the Polynesian Society, 93(3), pp. 267-281.

Thank you for the follow : ) Great article. I took part in the ’75 hikoi and was there at Raglan when they staked it out. The beginnings of my real education.

LikeLike

Ohh wow, i would love to hear you tell me about that! All i have is textbooks and trying to figure out what you activists were up to. My generation would never bother for such a march like that, protesting injustice itself seems to be pretty ‘uncool’ now

LikeLike

I’d have to disagree with you about your generation … there’ve been more recent hikois on eg the Foreshore & Seabed debacle. And other. I know a lot of activists who are doing same on other issues (TPPA eg). I was only 25 at the time of the ’75 hikoi but had been active in the HART and CARE movements. It certainly was an active decade. In all, raising awareness, hitherto submerged, about our true state of land loss. And dispelling the myth we had ‘the best race relations in the world’. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

BTW there are two docos on the hikoi as well. One screened recently then there was the original coverage. both excellent. Will try n find the links tomorrow : )

LikeLike